Might dusty, almost forgotten objects in Oxford’s Department of Physiology be somehow linked to one of the most notorious crimes of all time? Can they tell us something about the man or men whose actions held women in an almost permanent state of fear in London’s East End from April 1888 to February 1891?

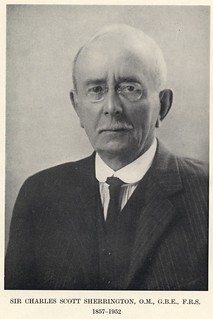

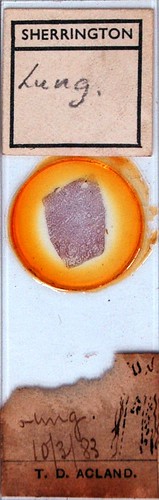

Among the rich and varied collection of microscope slides amassed by the Waynflete professor of physiology, Sir Charles Sherrington, during the course of his long and illustrious career, a considerable number is attributed to a certain ‘T. D. Acland’ and some of those also bear the label of St Thomas’s Hospital in London. Admittedly, these facts in themselves are not overly exciting, but then they are just the starting point of our story.

Sherrington’s career began when he entered St Thomas’s as a ‘perpetual pupil’ in 1876. To today’s medical undergraduates this might sound like an intriguing prospect, but in the London medical schools in the mid-nineteenth century this kind of perpetuity was simply a set of privileges obtainable against payment of a composition fee. At St Thomas’s it gave the young Sherrington admittance to hospital practice and lectures for an unlimited period. What actual benefit such status provided is hard to say, but Sherrington had been elected Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) and was teaching anatomy at St Thomas’s already by 1879.

Taking all these biographical details together, it is not surprising to find slides originating from that institution in his collection. More to the point, it is also not surprising that some of those slides also have printed labels bearing Acland’s name, since Theodore Dyke Acland (1851-1931) was a contemporary of Sherrington’s at the London Hospital.

One of the Sherrington slides containing stained lung tissue has an Acland label beneath the mount and a Sherrington label at the top. To these bare details on ownership Acland has supplied in ink on his label the information ‘lung 10/3/83’, while Sherrington has written in ink on his label simply ‘lung’. With the help of what Acland has written, we can assume that he produced the slide soon after graduating from Oxford with a doctorate in medicine in 1883. Indeed, we know that he was registered as a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (LRCP) in the same year. A decade later, he was appointed physician at St Thomas’s in 1893 and went on to become consultant physician and governor there.

Acland’s background and politics were quite different to those of Sherrington and after the First World War their relations which were probably not good at the best of times broke down completely. While Acland came from an aristocratic family in Devon with good social connections, Sherrington was raised in a middle-class family in East Anglia. While Acland was educated at Winchester and Christ Church, Oxford, his father’s college, Sherrington attended the local grammar school. To top it all, Acland’s father was regius professor of medicine at Oxford and served for some fourteen years as president of the General Medical Council: quite an advantage for young Theodore, we can presume. Nonetheless the early careers of Acland and Sherrington display distinct similarities. Both men spent time in Germany after graduating, researching in universities and specialist institutes, and both men were required to participate in overseas missions investigating contemporary outbreaks of cholera – Sherrington travelled to Spain and Italy in 1885 and 1886 respectively, while Acland went to Egypt in 1883. Subsequently, Acland developed even closer ties to the African continent, becoming first principal medical officer with the Egyptian army and later medical advisor to the colonial government in Sudan.

Both men were too old to enter active military service when war broke out in 1914, but their attitudes towards reconciliation after the signing of the Armistice could not have been more different. Acland argued vehemently for the total exclusion of German scholars from the Physiological Society and vented his anger on Sherrington, the Society’s president, for refusing to follow him. Sherrington on the other hand concurred with Albert Einstein, one of his many correspondents, that scientific collaboration might play an important role in rebuilding bridges between the allies and their former enemies. But this is not to say that for Sherrington that chapter of conflict was simply closed. Even in late 1918 he openly criticized those German intellectuals, including Paul Ehrlich and Max Planck, who had signed the infamous ‘Aufruf an die Kulturwelt’ of September 1914, expressing support for the Kaiser’s war policy. It was to that appeal that Einstein responded with his ‘Aufruf an die Europäer’. For Sherrington looking across to Germany it was a question of individual responsibility, while Acland sought to hold the whole nation to account.

And where does Jack the Ripper come into our story of two modern-day physiologists? As befitted his social status, Acland married Caroline Cameron Gull, the daughter of Sir William Gull 1816-90), this marriage taking place when he was well on the way to establishing his name in medicine in April 1888. It was later in that year that Jack the Ripper committed the first of his series of brutal crimes. Among the various theories proposed on the Whitechapel murders perhaps the most prominent, but since discredited, identifies none other than William Gull as accessory, his patient, Prince Albert Victor, duke of Clarence (1864-92) as the murderer himself. Apart from being one of the most prominent members of the medical profession in the second half of the nineteenth century, including Fullerian professor of physiology, Gull also happened to be Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria, Albert’s grandmother. The aptly-named ‘royal conspiracy theory’ also notes the questionable role played by Theodore Acland, who unethically, but not illegally, signed the death certificate of his father-in-law in January 1890. Was Acland part of a despicable cover-up? Almost undoubtedly not. But the theory continues to appeal to those inclined to suspect conspiracies where all the available evidence falls short. We might choose to reserve judgment on Acland’s behaviour, but let us not forget the important work of his father in law on anorexia nervosa, on paraplegia, and above all his undaunted efforts to support women entering the medical profession in late Victorian Britain.

G. H. Brown, Lives of the fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, 1826-1925. Volume 4, London 1955

L. Perry Curtis, Jack the Ripper and the London Press. New Haven 2001

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters